As faculty have endeavored to get traditional campus-based courses up and running remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic, the immediate needs of sharing course content with students, delivering lectures, and providing access to course materials were likely the top priorities. This approach makes sense, especially in the preparatory period before a class begins or when an instructor is getting ready to shift from on-campus to remote teaching.

However, it’s important not to stop there. Providing access to content is a great first step, but access on its own does not make for a quality learning experience. Engaging students is essential for promoting a deep understanding of course content. But how can we engage students in remote learning environments?

Shannon Riggs, executive director of academic programs and learning innovation, OSU Ecampus

There has already been discussion in the higher education community about how online education and remote instruction are not synonymous. Online educators, sensitive to skepticism about the efficacy of online education, are concerned that faculty who have negative perceptions of online education will associate problems with emergency remote education with non-emergency online course design and teaching. Higher education professionals have cautioned against equating remote and online delivery methods.

While online and remote education may not be synonymous, today’s new remote educators can benefit from the “lessons learned” by experienced online educators who are providing high-quality, engaging learning experiences for their students. The one “lesson learned” I see as the most significant for faculty as they begin to teach from a distance is to consider the new learning environment from a student-centered perspective.

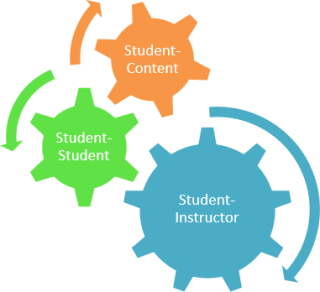

Many online educators have found that a helpful way to think about teaching in a student-centered fashion is to focus on creating three forms of interaction for students in the online environment:

- Student-content interaction, where instructors provide active learning experiences for students (meaningful learning activity plus reflection)

- Student-student interaction, where instructors structure the learning community and make it clear to students how they should interact with others in the class

- Student-instructor interaction, where instructors create a framework for how they will interact with students during the learning experience

These three forms of interaction don’t happen spontaneously. They require planning, intention, and instructional design. Furthermore, these three types of interaction aren’t prescriptive—they do not require the use of a particular type of learning activity or assessment. Through these interactions, we are reaching for broad goals that can be achieved in many different ways.

Finally, it’s important to recognize that the three forms of interaction do not require a specific set of enterprise-wide educational technologies. To put a student-centered approach to teaching into action, educators need to take stock of the tools and technologies they have available and then ask themselves three questions about how to use them.

Three questions to consider in student-centered remote teaching

To take a student-centered approach to remote teaching, consider the tools you have at your disposal, and ask three questions about your course:

- How will my students interact with the course content? Beyond reading, listening to/viewing lectures, what will students actually DO with the course content? And how can they do so in their homes?

- How will my students interact with other students? Beyond completing assignments and assessments independently, how will students work together to ensure that they feel like they are part of a learning community and have the opportunity to collaborate, think critically, be intellectually challenged, and make meaning with others? And how can students work with others while they are isolated in their homes?

- How will my students interact with me, their instructor? Now that you aren’t in the classroom with your students, how will students be able to interact with you? How might you guide student learning while also being flexible and trying to accommodate different student needs? What assignment expectations do you need to convey? What information do you need to clarify for students?

Asking these questions can help you see the course from the student’s point of view and think about remote teaching in a new way. When preparing a course for remote delivery, sharing course content online can feel overwhelming. It can be helpful to extend your thinking beyond content delivery to these three forms of student interaction.

In online course design, a lot of time and effort is invested in creating an architecture of engagement where these three forms of interaction can take place. The current health crisis has not allowed for the amount of development time any of us would have preferred, but there are some easy-to-implement instructional methods that you can use to help encourage student engagement when delivering courses remotely.

Student-content interaction

Student-content interaction is all about having students DO something with the course content or topic. Reading and listening to lectures will be part of many classes, but the passive receipt of information isn’t sufficient to help students engage with the course and meet course learning outcomes. Instead, we should create opportunities for active learning, which is when students DO something meaningful related to the course content and then reflect on their learning.

After students complete a course reading, ask them to do a follow-up assignment. Here are a few examples:

- Write a summary.

- Create an annotated visual on a PowerPoint slide that shows your key take-away from the reading.

- List five of your take-aways and one question you have based on the reading.

- Identify what you as a reader find to be the clearest point in the reading and the muddiest point

- Diagram a process.

- Make an infographic.

- Write an op-ed based on the content.

After students attend a synchronous lecture via web conference, ask them to complete a follow-up activity:

- Participate in a “think-pair-share” activity: The instructor poses a question, asks students to jot some notes down independently to form initial thoughts, distributes students into breakout rooms to discuss, and then pulls the class back together as a group to discuss and synthesize.

- Complete a poll to check comprehension.

- Illustrate ideas on the web conference whiteboard.

- Flip the web conference “lecture” by asking students to come prepared to discuss topics they have already read up on.

- Give students the opportunity to lead a discussion.

Other learning activities will vary by discipline and level of study. Consider these examples for inspiration:

- Completing kitchen lab experiments and lab reports

- Doing backyard or video “field” observations and field reports

- Analyzing data sets and creating data visualizations

- Preparing and giving multimedia presentations, including Q&As from classmates

- Creating infographics, web pages, blog posts, collages, memes, or digital images related to course content

Student-student interaction

When students interact with each other, they feel like they are part of a learning community, but this interaction also helps students engage in higher-order thinking that would be more challenging to accomplish if they were studying alone. Through collaboration, students brainstorm, deliberate, disagree, compromise, and achieve consensus—all ways of thinking that are difficult to do singly.

When you are remote teaching, consider employing some of the following strategies to encourage effective student-student interaction:

- Discussion forums in a learning management system

- Ask students to participate in a role-play or debate activity using online forums or web conference tools.

- Peer review activities for writing assignments and projects

- Group projects

- Group presentations

- Think-pair-share

- Study groups

- Individual projects

- Ask students to create a resource guide for future students.

- Ask students to design a board game based on course content.

- To facilitate this project, you could suggest that students adapt or create a trivia game, board game, etc.).

Students can arrange their own meetings, or they may choose to use other video conference solutions such as Skype. They can collaborate using Google Drive, Box, or other web-based tools.

Student-instructor interaction

The third form of interaction is student-instructor interaction, which should involve more than just answering student questions. For fully online classes, the US Department of Education requires that instructors provide regular, substantive, and instructor-led interactions to distinguish online classes from correspondence courses. These guidelines help online instructors provide strong student-instructor interaction. Remote instructors can use these guidelines to help engage students, too.

Some examples of how to facilitate student-instructor interaction when remote teaching follow:

- Participate and engage with students about the course content via discussion forums in a learning management system.

- Record and post a short video to introduce a major assignment and then hold a Q&A session.

- Provide detailed feedback on assignments (written and/or recorded).

- Use voice-over screen recordings using tools such as Screencast-O-Matic to provide demonstrations, discussions of diagrams/graphs, slides, and illustrations.

- Hold writing conferences to discuss draft assignments.

- Hold open or by-appointment office hours by web conference, phone, or text message.

- Create a video (with your pets, family, etc.) in your home or a safe outdoor environment to provide social presence.

While remote instruction during an emergency pandemic is not the same as carefully designed online education, remote educators can take some notes from experienced online colleagues about how to bridge the distance. Thinking of the learning experience from a student-centered perspective is one valuable take-away. There are many, many others.

Author’s note: Thanks to Clare Creighton, Dorothy Loftin, Deborah Mundorff, Meghan Naxer and Weiwei Zhang for their contributions to this blog post.

Editor’s note: This blog post was originally published by the EDUCAUSE Review, and an earlier version was published online by Oregon State University’s Center for Teaching and Learning.